Click here for more information

When it comes to relying on spreadsheets for day-to-day business, that old idiom, “better the devil you know, than the devil you don’t”, seems to be the orthodox mantra. Numerous studies indicate that more than 70% of organizations repeat the mantra of using spreadsheets as their daily financial information bread and butter — despite the fact that spreadsheets can quickly be outgrown and can become onerous task masters.

In one 2004 survey by CFO Research Services, respondents across the board (>60%) reported that they spend too much time on forecasting, budgeting, and planning — time spent inside their beloved, yet despised, spreadsheets. 43% reported that they don’t have enough time to analyze the data that they have collected.

Earlier this year, Oracle and Accenture commissioned a research study on the challenges of corporate financial reporting with input from more than 1,100 large organizations across the US, Europe, Middle East and Africa. More than 60% reported inadequate visibility into financial data. More than 80% say it is difficult to control the quality of financial data and other supporting information. Yet, spreadsheets and email are still used by more than 68% of these respondents to track and manage reporting.

CULPRITS

What are some of the culprits for this disconnect between current methods of sharing data and with controlling quality?

The CFO study found that the biggest problem was over dependence on key personnel (nearly 50 % of respondents). These people are overburdened. And from a corporate memory perspective, the organization might have too many mission critical processes trapped in too few personnel minds — risking business disruption if those key personnel no longer can perform their duties.

More than 35% of the CFO study respondents reported that version control was their biggest problem. Too many different versions of similar Excel spreadsheet data are floating around in that corporate mindspace of file shares and email. User collaboration and data consolidation are related to this same version control issue — another 35% of respondents reported these as problematic.

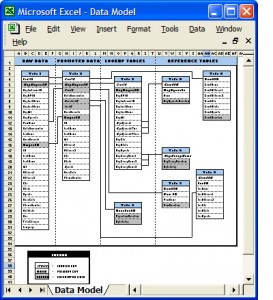

Complexity is another bugaboo. Just because you are capable of doing something does not mean that it is a good idea. We have clients who have come to us with Excel workbooks containing hundreds of worksheets, drowning their users in unmanageable and unresponsive data. Just because Excel can hold hundreds of worksheets does not mean that you should base your reporting infrastructure on that ability. Why, there’s even a Tetris game created within Excel, to add to the absurd lengths some people will go to stay wed to spreadsheets.

Are you drowning in spreadsheets and need a lifeline? Give us a call.